J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. (2007)03-0301-04

DOI: 10.1007/s11771-007-0059-3

Synthesis and structural characterization of macroporous bioactive glass

ZHOU Zhi-hua(周智华)1,2, RUAN Jian-ming(阮建明)1, ZOU Jian-peng(邹俭鹏)1,

ZHOU Zhong-cheng(周忠诚)1, SHEN Xiong-jun(申雄军)1

(1. State Key Laboratory of Powder Metallurgy, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China;

2. College of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Hunan University of Science and Technology,

Xiangtan 411201, China)

Abstract: Porous sol-gel glass of CaO-SiO2-P2O5 system with macropores larger than 100 μm was prepared by adding stearic acid as pore former when the sintering was carried out at 700 ℃ for 3 h. The sol-gel porous glass shows an amorphous structure. The diameter of the pore created by pore former varies from 100 to 300 μm, and macroporous glass has a narrow and small pore size distribution in mesoporous scale. The porosity and pore size of macroporous bioactive glass can be controlled.

Key words: macroporous glass; sol-gel method; synthesis; structural characterization

1 Introduction

The discovery of melt derived 45S5 bioactive glass opened a novel research area on glasses for bone repair and substitution[1]. Bioactive glasses can bond to both bone and soft tissue and can stimulate bone growth. The bone bonding ability of the glasses attributes to their ability to form a surface layer of hydroxycarbonate apatite (HCA)[2-3]. So they have been widely used in many different applications[4-5].

A few methods have been developed to prepare the bioactive glass. Melting method is the traditional one. It is simple and suitable for massive production. However, during the high temperature stage, the volatile component P2O5 tends to escape. In recent years, sol-gel method has attracted attention of many scientists. Compared with the melting method, the sol-gel processes have the advantages of low reaction temperature and homogenous composition in particles. Sol-gel derived bioactive glasses of SiO2-CaO-P2O5 system have been widely studied[6-8].

Although bioactive ceramics have achieved great successes in bone repairing, some researchers pointed out that the emphasis of biomedical material research should be shifted towards assisting or enhancing the body’s own repair capacity. The future of bioceramics should be the scaffold for bone tissue engineering. An ideal scaffold should be a macroporous material with two important characteristics: the first, a cross-linking with large pores (more than 100 μm) to enable tissue in growth and nutrition delivery to the center of the regenerated tissue; the second, pores in the microporous or mesoporous range to promote cell adhesion, adsorption of biologic metabolites, and restorability at controlled rates to match that of tissue repair.

Macroporous silica glasses with the pore diameter less than 10 μm have been prepared by different methods[9-10]. However, it is very difficult to produce macroporous sol-gel glasses with a pore size larger than 100 μm because of the great shrinkage during sol-gel processing. JIE et al[11] reported a method to prepare macroporous sol-gel bioactive glasses with pores larger than 100 μm. In the last few years, the successful applications of pore former in the gel drying have made it possible to prepare macroporous sol-gel. In this work, macroporous sol-gel bioactive glass using granular stearic acid as pore former was prepared and the structure was characterized.

2 Experimental

The composition(molar fraction) of porous glass is: SiO2 (60%), CaO (35%), P2O5 (5%), where SiO2 and P2O5 are the network formers, while CaO acts as network modifiers. Sol was prepared from teraethylortosilicate (TEOS), with deionized water as solvent, hydrochloric acid as catalyst, and calcium nitrate and triethyl phosphate(TEP) as CaO and P2O5 precursors, using a molar ratio of (HCl + H2O/ TEOS + TEP = 8). The synthesis was made at a low pH causing a spontaneous gelation owing to hydrolysis of TEOS and subsequent condensation of formed Si—OH groups. The sol was kept for 3 d at room temperature to allow the hydrolysis and polycondensation reactions until the gel was formed. For aging, the gel was heated at 60 ℃ for 3 d. The dried gel was heated at 160 ℃ for 2 d, then ground for 8 h and sieved to 60-75 μm. The stearic acid was sieved as pore former before experiment and the size range of 150–350 μm was chosen. Fractions of powder, adding 7% polyvinyl alcohol(PVA) as an organic binder, were compacted at uniaxial pressure at room temperature to obtain disks (12 mm in diameter and 12 mm in height). The sintering temperature was determined by thermogravimetric and differential thermal analyses (TG/DTA) of the dried gel were carried out in a Seiko Thermoblance WCT-20 from 25 ℃ to 1 200 ℃ at 10 ℃/min in air.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern was obtained using a Philips PW1700 series automated XRD spectrometer, with Cu Kα radiation. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (JEOL, JSM 6360LV) on gold-coated specimen was used to examine the morphological and textural features of the sample, with an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. The microstructure analysis was made by nitrogen adsorption technique (Tristar 3000, Micromeritics, USA). Before this experiment, small specimens were heated to 200 ℃ for 3 h under the protection of nitrogen gas flow to remove moisture from pores, and then the accurate mass of the samples was recorded. The volume of nitrogen adsorbed and desorbed at different relative pressures was measured, generating isotherm curves. The pore diameter distribution was calculated by the BJH method applied to the desorption curves. Larger pore size distributions were determined by intrusion mercury porosimetry (Poresizer 9320, Micromeritics, USA). Compression tests were carried out on cylindrical foams, with heights of 12 mm and diameters of 12 mm using an Instron with a cross-head velocity of 0.5 mm/min and 1 000 N load cell. Three samples were used for each group and mean values were taken.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Determination of sintering temperature

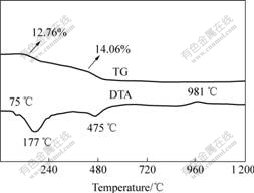

In Fig.1 the TG/DTA curves of the gel, after being dried at 60 ℃ for 3 d and 160 ℃ for 2 d, are shown. On the TG curve between room temperature and 177 ℃ a first mass loss of 12.76% is observed. A second mass loss of 14.06% occurs from 177 to 550 ℃. Then the mass remains almost constant up to 1 200 ℃.

On the DTA curve, three wide endothermic peaks at 75, 177 and 475 ℃, as well as one exothermic peak at 981 ℃, can be observed. The first endothermic process may be attributed to the elimination of humidity from the atmosphere, and the second endothermic peak at 177 ℃ to the elimination of humidity and organic compound. The endothermic peak at 475 ℃ may be due to the elimination of the nitrates introduced as calcium nitrate in the preparation of sol. These results agree with those of DUVAL[12], which indicates that calcium nitrate is stable up to 475 ℃ and above that temperature the elimination of NO2 starts. The exothermic maximum at 981 ℃ may be due to the crystallization. According to previous research[13], stearic acid is eliminated between 280 ℃ and 500 ℃. To enhance the possible bioactivity of glass, the lowest temperature of the interval, that is 700 ℃, is chosen for the heat treatment. The dried gel disks were heated from 25 to 700 ℃ at 5 ℃/min in air, and the stabilization treatment was carried out at 700 ℃ for 3 h.

Fig.1 TG/DTA curves of gel powder after being dried

3.2 Structure of porous glass

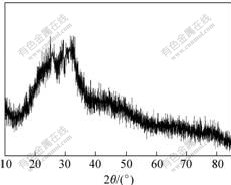

The XRD pattern of the surface macroporous glass is shown in Fig.2. The result confirms the absence of crystalline phases in the sample, because no diffraction peak is observed and only a broad band between 10? and 50? is detected for the gel bioactive glass.

Fig.2 XRD pattern of macroporous glass

Fig.3 shows typical SEM micrographs of the macroporous glass. An ideal pore structure is shown clearly, exhibiting a homogeneous interconnected macroporous network with open pores. The pore sizes are in the range of 100-300 μm. It is not only large enough for cell’s attachment, but also suitable for tissues and blood vessels to grow in. From the magnified image, we can see that these large pores interconnect through channels of smaller ones on their wall. The diameters of these smaller pores vary from 1 to 10 μm (seen in Fig.3(c)). They may come from the PVA dissolved into sol during the mixing procedure.

Fig.3 SEM micrographs of porous bioactive glass(a) and (b) Low magnification; (c) High magnification image of site painted by arrow in (b)

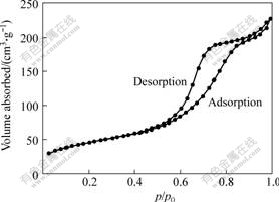

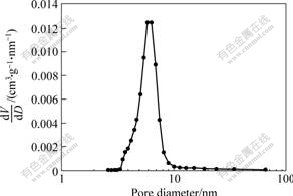

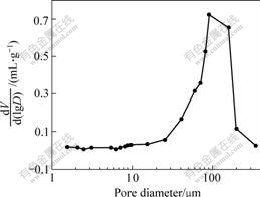

In the pore structure analysis, the specific surface area of macroporous bioactive glass is 130.48 m2/g. Fig.4 shows the nitrogen sorption isotherm plots of the sample. An isotherm is the relationship, at constant temperature (77 K), between the amount of gas adsorbed (usually expressed in cm3/g) and the relative pressure p/p0, where p0 is the saturation pressure of pure nitrogen. According to BDDT classification[14], the isotherms obtained from foam are of type II, implying that the sample contains mesopores, i.e. pores with diameters in the range of 2-50 nm[15]. A steep slope at high relative pressure is associated with capillary condensation in the pores and a narrow pore size distribution. The hysteresis loop between adsorption and desorption mode is associated with capillary condensation in the mesopore structure. Fig.5 presents the dV/dD(V: Pore volume; D: Pore size diameter) pore distribution of porous specimen, which indicates that macroporous glass has a narrow and small pore size distribution in mesoporous scale.

Fig.4 Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherm plot of macroporous glass

Fig.5 Mesopore distribution of macroporous glass

Fig.6 shows the macropore-size distribution of macroporous sol-gel glass by mercury porosimetry. The large pore ranges from 100 to 300 μm. The average pore diameter is 55.75 μm and the pore volume is 0.435 mL/g measured by low pressure mercury intrusion porosimetry. At the same time, the pore size distribute around 1-10 μm confirms the phenomena observed by SEM.

Table 1 presents the effect of forming pressure on the dimension shrinkage, porosity and compressive pressure of samples added with 20% stearic acid. The dimension shrinkage of porous specimens during the sintering process decreases with increasing the forming pressure, however, the porosity and compressive pressure increase when the forming pressure increases. As pore former, the stearic acid particles added into gel can prevent dimension shrinkage. After sintering, the average shrinkage in dimension of the samples is about 30%. The samples added with stearic acid porosifier will not relapse after being compacted because stearic acid particles are plastic[13]. The deformability of plastic porosifier will increase and the samples will be more compacted with increasing forming pressure, therefore, the compressive strength will increase. The shrinkage will decrease during sintering, and the open porosity will increase when the shrinkage of pore wall decreases.

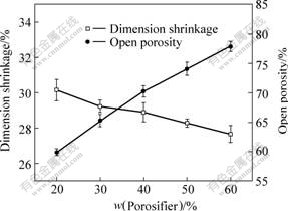

Fig.7 shows the effect of content of stearic acid porosifier on dimension shrinkage and open porosity of samples under 250 MPa forming pressure. The dimension shrinkage decreases slowly, however the open porosity increases quickly with increasing the content of

Table 1 Effect of forming pressure on dimension shrinkage (n=3), porosity (n=3) and compressive pressure (n=3) of samples added with 20% stearic acid porosifier

n: number of specimens of each material group

Fig.6 Macropore-size distribution of macroporous sol-gel glass by mercury porosimetry

Fig.7 Dimension shrinkage and open porosity of samples as function of content of stearic acid porosifier (n=3)

stearic acid porosifier. The open porosity reaches about 78% when the content of stearic acid porosifier is 60%(mass fraction), which indicates the porosity of macroporous bioactive glass can be controlled.

4 Conclusions

1) A sol-gel macroporous bioactive glass was obtained by adding stearic acid particles as pore former.

2) The porous bioactive glass fabricated has macropores larger than 100 μm and has a narrow and small pore size distribution in mesoporous scale. With increasing forming pressure, the dimension shrinkage of macroporous specimens during the sintering process decreases, however, the porosity and compressive pressure increase. The dimension shrinkage decreases, however the open porosity increases with increasing content of stearic acid.

3) The material could serve as 3-D scaffold for cells.

References

[1] HENCH L L. Bioceramics[J]. J Am Ceram Soc, 1998, 81(7): 1705-1728.

[2] OHURA K, NAHAMURA T, KOKUBO T, et al. Bone-bonding ability of P2O5-free CaO-SiO2 glasses[J]. J Biomed Mater Res, 1991, 25(3): 357-365.

[3] ZHONG J P, GREENSPAN D C. Processing and properties of sol-gel bioactive glasses[J]. J Biomed Mater Res, 2000, 53(6): 694-697.

[4] VALLET-REGI M. Ceramics for medical applications[J]. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans, 2001, 17: 97-108.

[5] HENCH L L. Bioceramics: From concept to clinic[J]. J Am Ceram Soc, 1991, 74(7): 1487-1510.

[6] ROMIAN J, PADILLA S, VALLET M. Sol-gel glasses as precursors of bioactive glass ceramics[J]. Chem Mater, 2003, 15(3): 798-806.

[7] PEREIRA M M, CLARK A E, HENCH L L. Calcium phosphate formation on sol-gel-derived bioactive glasses in vitro[J]. J Biomed Mater Res, 1994, 28(6): 693-698.

[8] SEPULVEDA P, JONES J R, HENCH L L. In vitro dissolution of melt-derived 45S5 and sol-gel derived 58S bioactive glasses[J]. J Biomed Mater Res, 2002, 61(2): 301-311.

[9] LIU Jian-li, MIAO Xi-geng. Sol-gel derived bioglass as a coating material for porous alumina scaffolds[J]. Ceramics International, 2004, 30(7): 1781-1785.

[10] JONES J R, AHIR S, HENCH L L. Large-scale production of 3D bioactive glass macroporous scaffolds for tissue engineering[J]. Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology, 2004, 29(3): 179-188.

[11] JIE Qing, LIN Kai-li, ZHONG Ji-pin, et al. Preparation of macroporous sol-gel bioglass using PVA particles as pore former[J]. Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology, 2004, 30(1): 49-61.

[12] DUVAL C. Inorganic Thermogravimetric Analysis[M]. New York: Elsevier, 1963: 274.

[13] HE Feng, LIU Chang-sheng. Preparation of porous glass-ceramic with controlled pore size and porosity by adding porosifier[J]. Journal of Inorganic Materials, 2004, 19(6): 1267-1276.(in Chinese)

[14] BRUNAUER S, DEMING L S, DEMING W E, et al. On a theory of the van der Waals adsorption of gases[J]. J Am Chem Soc, 1940, 62: 1723-1732.

[15] SING K S W, EVERETT D H, HAUL R A W, et al. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems[J]. Pure Appl Chem, 1985, 57(4): 603-619.

(Edited by YANG Bing)

Foundation item: Project(50174059) supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China

Received date: 2006-06-24; Accepted date: 2006-09-27

Corresponding author: RUAN Jian-ming, Professor, PhD; Tel:+86-731-8876644; E-mail: jianming@mail.csu.edu.cn