Low-cyclic fatigue properties of electrolytic low-titanium A356 alloys

LIU Zhong-xia(刘忠侠), SONG Mou-sheng(宋谋胜), WENG Yong-gang(翁永刚), WANG Ming-xing(王明星),

SONG Tian-fu(宋天福), LIU Zhi-yong(刘志勇)

Key Laboratory of Material Physics of Ministry of Education, School of Physics Engineering,

Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450052, China

Received 28 July 2006; accepted 15 September 2006

Abstract: The low-cycle fatigue (LCF) behavior of two kinds of A356 alloys produced by different titanium alloying methods was investigated and compared. The effect of titanium content and titanium alloying methods on LCF behavior is analyzed with plastic strain energy density. The results show that all alloys exhibit the cyclic hardening behavior. Raising Ti content can obviously increase the cyclic hardening ability. But the effect of Ti alloying method isn’t distinct. Whether for the EA356 alloys or for MA356 alloys, the alloys with low titanium content have longer low-cycle fatigue life than that of the alloys with high titanium content. This is because that the alloys with low titanium content can consume higher cyclic plastic strain energy during cyclic deformation compared with alloys with high titanium content.

Key words: electrolytic low-titanium A356 alloys; low-cyclic fatigue properties; cyclic plastic strain energy density

1 Introduction

The A356 alloys have been widely used in the automotive to meet the growing demand for components and structures with high strength and low mass [1]. To successfully use such an alloy in components intended for long life applications, it is necessary to understand its fatigue resistance. It has been found that the fatigue crack always initiates from the porosities, inclusions, shrinkage cavities and oxide films under the cyclic load [1-3]. The microstructure of alloys has an important effect on the fatigue properties of alloys. Refining the microstructure and modifying the eutectic silicon particles are favorable to prolong the fatigue life of alloys [4-7]. But the effect of solidification structure is small [8-9], especially when the second dendrite arm spacing (SDAS) is less than 30 μm. The SDAS almost has not any effect on the low-cyclic fatigue(LCF) life of A356 alloys[10]. In this paper, two kinds of A356 alloys with different titanium contents are produced with pure aluminium and low-titanium aluminium alloys. The LCF experiments of tested alloys are carried out. The effect of titanium alloying method and titanium content on the fatigue properties are investigated. The difference of LCF behavior among the tested alloys is analyzed with cyclic plastic strain energy density.

2 Experimental

The tested A356 alloys were produced by two kinds of titanium alloying methods respectively. One was directly produced by in-situ titanium alloying Al-0.28%Ti alloys which were produced by electrolysis, named electrolytic low-titanium A356 alloy (EA356). Another was produced by pure aluminum and Al-5Ti master alloys, named traditional A356 alloys (TA356 alloys). All A356 alloys had the same Si, Mg content and were treated by the same T6 heat treatment process. The chemical composition and the tensile properties of tested alloys are represented in Table 1.

The low cycle fatigue properties of alloys were measured at ambient temperature with a reversed triangular waveform (total strain range from 0.002 to 0.009) and a frequency of 1 Hz. All tests were conducted on the MTS810 tester. The smooth samples with a diameter of 8 mm and a gauge length of 16 mm were used. The microstructure and fracture surface of tested alloys were examined using Philips-210 transmission electron microscope (TEM) and JSM-5600 scanning electron microscope (SEM).

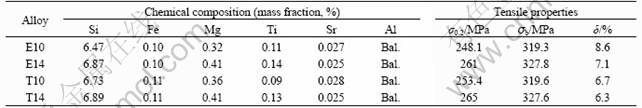

Table 1 Chemical composition and tensile properties of tested A356 alloys

3 Results

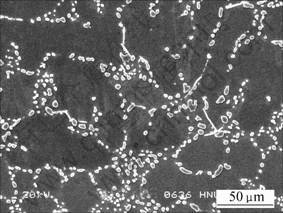

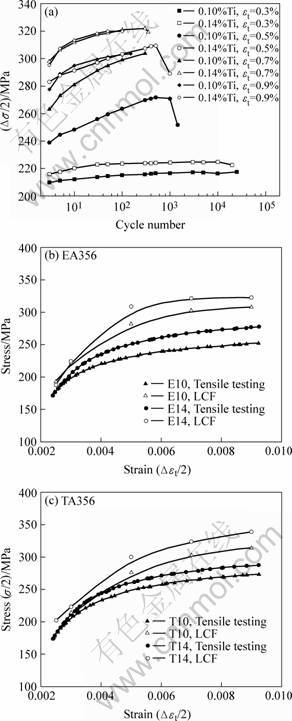

Fig.1 shows the typical microstructure of EA356 alloys. The microstructure parameters are shown in Table 2. The EA356 alloys have finer primary dendrite and silicon particles than that of TA356 alloys. Two kinds of alloys have the similar SDAS, which is 23-25 μm. Fig.2 shows the cyclic stress—strain curves of EA356 alloys. The stress—plastic strain curves obtained by monotonic tensile tests were also shown for comparison. All alloys show the cyclic hardening behavior. Raising Ti content can obviously increase the cyclic hardening ability. The effect of Ti alloying method isn’t distinct. The similar cyclic stress—strain curves of TA356 alloys can be obtained.

The cyclic hardening behavior is very sensitive to the solidification structure and aging hardening condition. The effect of microstructure on the cyclic hardening of alloys is mainly attributed to their influence on the degree of interaction among dislocation, eutectic particles, and dendrite cell/grain boundaries [10-13]. In this test, two kinds of A356 alloys have similar SDAS. But the refinement effect of grain and silicon particles among the tested alloys is different (see Table 2). The cyclic hardening behavior of A356 alloys with finer microstructure is dominated by the dendrite cell size or grain size. The dislocation slip distance corresponds to the dendrite cell size or grain size. Refining the grain size increases the resistance of dislocation across the grain boundaries, which results in the increase of the cyclic hardening of alloys. HAN et al[10] found similar results in the investigation of low-cycle fatigue of A356 alloys. They found that refining the microstructure can increase the cyclic hardening of alloys when SDAS <60 μm.

Fig.1 Microstructure of EA356 alloys

Fig.2 Cyclic hardening curves of A356 alloys: (a) Variation of stress amplitude for strain cycling; (b) and (c) Monotonic and cyclic stress—strain curves of EA356 alloys and TA356 alloys respectively

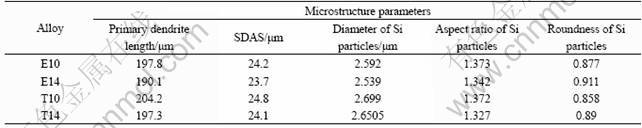

Table 2 Microstructure parameters and tensile properties of A356 alloys

The low-cycle fatigue behavior of alloys can be described reasonably with cycle plastic strain energy density. The cyclic plastic strain energy density of alloys is the energy consumed per cycle of alloys during cycle deformation, which is defined as [14-15]:

(1)

(1)

where Δεp and Δσ are the cyclic plastic strain amplitude and cyclic stress amplitude respectively; n′ is the cyclic strain-hardening exponent. The fatigue resistance of the alloys can be analyzed in terms of Halford–Marrow power-law relationship:

(2)

(2)

where  and β are material constants, which can be used to evaluate the fatigue resistance of alloys.

and β are material constants, which can be used to evaluate the fatigue resistance of alloys.

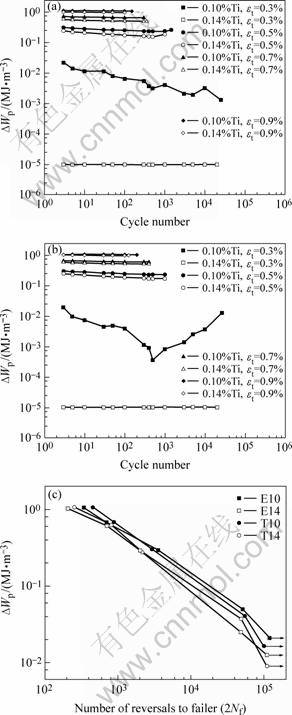

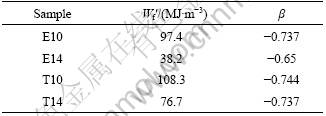

Fig.3 shows the relation of cyclic plastic strain energy density and cycle number of tested alloys. The values of  and β are shown in Table 3. It can be found that the influence of titanium content on the cyclic plastic strain energy density is obvious. Compared with alloys E14 and T14, alloys E10 and T10 have higher cyclic plastic strain energy density and higher values of

and β are shown in Table 3. It can be found that the influence of titanium content on the cyclic plastic strain energy density is obvious. Compared with alloys E14 and T14, alloys E10 and T10 have higher cyclic plastic strain energy density and higher values of  and β (as shown in Table 3). The fatigue life of alloys E10 and T10 is longer than that of alloys E14 and T14. When tested at the condition of Δεt/2<0.3%, a certain quantity of cyclic plastic strain energy can be still consumed in alloys E10 and T10, but in alloys E14 and T14, the consumption of cyclic plastic strain energy is little. It is clear that the tested alloys with low titanium content can consume higher cyclic strain energy compared with the alloys with higher titanium content. But the influence of titanium alloying method on the cyclic plastic strain energy density and fatigue life is unapparent. The alloys EA356 and TA356 almost have the same fatigue life if the tested alloys have the same titanium content.

and β (as shown in Table 3). The fatigue life of alloys E10 and T10 is longer than that of alloys E14 and T14. When tested at the condition of Δεt/2<0.3%, a certain quantity of cyclic plastic strain energy can be still consumed in alloys E10 and T10, but in alloys E14 and T14, the consumption of cyclic plastic strain energy is little. It is clear that the tested alloys with low titanium content can consume higher cyclic strain energy compared with the alloys with higher titanium content. But the influence of titanium alloying method on the cyclic plastic strain energy density and fatigue life is unapparent. The alloys EA356 and TA356 almost have the same fatigue life if the tested alloys have the same titanium content.

Fig.3 Relation of cyclic strain energy density vs cycle number: (a) and (b) Relation of cyclic strain energy density vs cycle number of EA356 and TA356 alloys; (c) Curve of cyclic plasticity energy density vs cycle number to failure of A356 alloys

Table 3 Parameters of plastic strain energy for A356 alloys

The change of cyclic plastic strain energy density is affected by the deformation mechanism of alloys at different strain amplitudes. At high strain amplitude, the tested alloy subjects to higher stress. The deformation mechanism of tested alloys is macro plastic deformation. At low strain amplitude, however, the interior micro plastic deformation of alloys is the dominant deformation mechanism. Therefore, the effect of plastic deformability of alloys on fatigue properties must be very important. If the difference of microstructure among alloys is small, the effect of ductility on the cyclic plastic strain energy density may be decisive effect factor on the fatigue resistance of alloys. Compared with Fig.3(c), it can be found that alloys E10 and T10 have longer fatigue life compared with that of alloys E14 and T14 even though the latter alloys have finer microstructure. The main reason is that the former alloys have high ductility. The micro plastic deformation of alloys can more easily take place. The cumulative stress produced by dislocation block can be easily relaxed. The initiation and propagation of fatigue crack need to consume higher plastic strain energy.

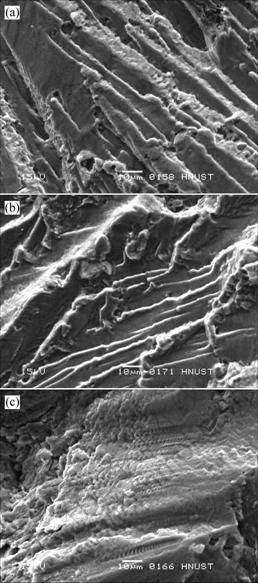

Fig.4 shows the fractographs of alloys E10 and E14 tested at low strain amplitude. The similar fractograph is also found in alloys T10 and T14. It can be found that though fatigue strip in the fractograph can be observed both in alloys E10 and E14 (Figs.4(a) and (b)), tyre patterns in fatigue strip are only found in alloy E10 (Fig.4(c)). Because the tyre pattern corresponds to the blunting-sharpening trace of micro fatigue cracks tips in microstructure, the appearance of tyre patterns means that higher ductility of alloy can increase the propagation resistance of fatigue cracks, which results in the phenomenon that the alloy E10 has higher fatigue life.

4 Conclusions

The low-cycle fatigue behavior of two kinds of A356 alloys was investigated and compared. All alloys show the cyclic hardening behavior. Raising Ti content can increase obviously the cyclic hardening ability. Whether for the EA356 alloys or for TA356 alloys, the low-cycle fatigue life of alloys with low titanium content is longer than that of the alloys with high titanium content. The reason is that the alloys with low titanium content have high ductility. The cumulative stress produced by pile-up of dislocation during deformation can be easily relaxed. The initiation and propagation of fatigue crack need to consume higher plastic strain energy, which effectively increases the low cyclic fatigue life of tested alloys.

Fig.4 Fractographs of A356 alloys: (a) Fatigue stripe in alloy E10; (b) Fatigue stripe in alloy E14; (c) Tyre patterns in alloy E10

References

[1] MILLER W S, ZHUANG L, BOTTEMA J, WITTEBROOD A J, DE SMET P, HASZLER A, VIEREGGE A. Recent development in aluminum alloys for the automotive industry [J]. Mater Sci Eng A, 2000, 280: 37-49.

[2] SIGWORTH G K, SHIVKUMER S, APELIAN D. The Influence of molten metal processing on mechanical properties of cast Al-Si-Mg alloys [J]. AFS Transaction, 1989, 97: 811-824.

[3] CHAN K S, JONES P, WANG Q. Fatigue crack growth and fracture paths in sand cast B319 and A356 aluminum alloys [J]. Mater Sci Eng A, 2003, 314: 18-34.

[4] WANG Q G, APELIAN D, LADOS D A. Fatigue behavior of A356/357 aluminum cast alloys (Part Ⅱ)-Effect of microstructural constituents [J]. Journal of Light Metals, 2001, 1: 85-97.

[5] ZHANG B, CHEN W, POIRER D R. Effect of solidification cooling rate on the fatigue life of A356.2-T6 cast aluminum alloy [J]. Fatigue Fact Engng Mater Struct, 2000, 23: 417-423.

[6] HAN S W, KUMAI S, SATO A. Fatigue crack growth behavior in semi-liquid die-cast Al-7%Si-0.4%Mg alloys with fine effective grain structure [J]. Mater Sci Eng A, 2001, 308: 225-232.

[7] CACERES C H, GRIFFITHS J R. Damage by the cracking of silicon particles in an Al-7Si-0.4Mg casting alloy [J]. Acta Mater, 1996, 44: 25-33.

[8] AVALLE M, BELINGARDI G, CAVATORTA M P, DOGLIONE R. Static and fatigue strength of a die-cast aluminum alloy under different feeding conditions[J]. J Materials: Design and Applications, 2002, 216: 25-30.

[9] STOLARZ J, MADELAINE-DUPUICH O, MAGNIN T. Microstructural factors of low cycle fatigue damage in two phase Al-Si alloys [J]. Mater Sci Eng A, 2001, 299: 275-286.

[10] HAN S W, KATSUMATA K, KUMAI S, SATO A. Effect of solidification structure and aging condition on cyclic stress—strain response in Al-7%Si-0.4%Mg alloys [J]. Mater Sci Eng A, 2002, 337: 170-178.

[11] WANG Q G, CACERES C H. On the strain hardening behavior of Al-Si-Mg casting alloys [J]. Mater Sci Eng A, 1997, 234-236: 106-109

[12] HORSTEMEYER M F. Damage influence on the Bauschinger effect of a cast A356 aluminum alloy [J]. Scripta Materialia, 1998, 39: 1491-1495.

[13] FAN J H, MCDOWELL D L, HORSTEMEYER M F, GALL K. Cyclic plasticity at porosities and inclusions in cast Al-Si alloys [J]. Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 2003, 70: 1281-1302.

[14] SANDER B I. Fundamental of Cyclic Stress and Strain [M]. The University of Wisconsin Press, 1972.

[15] PRASAD N E, VOGT D. High temperature, low cycle fatigue behaviour of an aluminium alloy (Al-12Si-CuMgNi) [J]. Mater Sci Eng A, 2000, 276: 283-287.

(Edited by YUAN Sai-qian)

Corresponding author: LIU Zhong-xia, Tel: +86-371-67767776; E-mail: liuzhongxia@zzu.edu.cn