Microstructure refinement of AZ91D alloy solidified with pulsed magnetic field

WANG Bin(汪 彬), YANG Yuan-sheng(杨院生), ZHOU Ji-xue(周吉学), TONG Wen-hui(童文辉)

Institute of Metal Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenyang 110016, China

Received 4 September 2007; accepted 24 December 2007

Abstract: The effects of pulsed magnetic field on the solidified microstructure of an AZ91D magnesium alloy were investigated. The experimental results show that the remarkable microstructural refinement is achieved when the pulsed magnetic field is applied in the solidification of AZ91D alloy. The average grain size of the as-cast microstructure of AZ91D alloy is refined to 104 mm. Besides the grain refinement, the morphology of the primary a-Mg is changed from dendritic to rosette, then to globular shape with changing the parameters of the pulsed magnetic field. The pulsed magnetic field causes melt convection during solidification, which makes the temperature of the whole melt homogenized, and produces an undercooling zone in front of the liquid/solid interface by the magnetic pressure, which makes the nucleation rate increased and big dendrites prohibited. In addition, primary a-Mg dendrites break into fine crystals, resulting in a refined solidification structure of the AZ91D alloy. The Joule heat effect induced in the melt also strengthens the grain refinement effect and spheroidization of dendrite arms.

Key words: AZ91D magnesium alloy; grain refinement; pulsed magnetic field; solidified microstructure

1 Introduction

A fine grain size is beneficial to structure uniformity and mechanical properties, which can be easily understood by considering the Hall-Petch effect. As the coefficient is fairly large for magnesium, a refined grain size would be very desirable in order to obtain improved properties for as-cast magnesium alloys[1]. For example, zirconium is often added in aluminium-free magnesium alloys as a potent grain refiner to improve the mechanical properties of the alloys. However, zirconium is noneffective in the alloys containing Al, Si, Mn, Ni or Fe[2]. Superheating and carbon inoculation have been reported to be effective for Mg-Al alloys[3]. The shortcoming of the superheating method is that additional energy is required to heat and hold the melt up to 150-260 ℃ above the melting point for a certain period of time so that the oxidation of the melt becomes severe at such high temperature. Carbon inoculation involves the introduction of carbon-containing substances such as C2Cl6, paraffin wax, which is usually accompanied by a large amount of harmful volatile matters released from the melt during the grain refining process[3]. There is no reliable grain refiner for Mg-Al alloys and thus the benefit of a much finer grains has not been reliably achieved[4].

Applying electromagnetic vibration to solidification of metals is a new method developed in recent years. VIV?S[5-7] applied an electromagnetic vibration to commercial aluminum alloys, and achieved microstructural refinement. RADJAI and MIWA[8-9] investigated the effects of the frequency and intensity of electromagnetic vibration on the microstructural refinement for Al-Si alloys. YANG et al[10] studied the microstructure evolution of AZ91D magnesium alloy solidified with various electric current pulses, and found that the electric current pulses during solidification changed the morphology of dendrites and resulted in the equiaxed, non-dendritic grains. Recently, BAN et al[11] applied a pulsed magnetic field(PMF) to the 2124 Al- alloy and found a remarkable change in the solidified structures. GAO et al[12] studied the structural trans- formation in low-melting pure Al under external PMF.

The experiments showed that totally equiaxed grains were produced for pure Al. Besides that, the PMF had many advantages, such as simple equipment, high efficiency, low cost, as well as low pollution because of the non-contact with the melt.

In this work, PMF is applied to the AZ91D alloy to change the solidified microstructure in order to find a simple and effective way to achieve grain refinement for Mg-Al alloys without adding refiner or refining elements. Furthermore, the effects of the process parameters of PMF on the average grain size and structures are investigated and the mechanism is analyzed.

2 Experimental

The commercial AZ91D alloy was selected. Its chemical compositions (mass fraction, %) were: Al 9.03, Zn 0.64, Mn 0.33, Be 0.0014, Si 0.031, Cu 0.0049, Fe 0.0011, Ni 0.0003, and balance Mg.

The experiment was carried out by using a PMF solidification setup. The AZ91D alloy was first remelted in an electrical resistance furnace using a mild steel crucible. The alloy was heated to 750 ℃ and kept for 10 min, then, the melt was poured into a pre-heated (to 400 ℃) graphite mould with a diameter of 50 mm, height of 80 mm and wall-thickness of 3 mm. The pulsed magnetic field was imposed to the melt until it completely solidified. Both the processes of melting and solidification were protected by the atmosphere of 0.5%SF6+99.5%CO2 from oxidation. Different pulsed- magnetic parameters were used in the experiments through changing discharge voltage, U, and pulse frequency, ω. Here, the pulsed magnetic parameter, a, is defined as the ratio of U to ω.

The specimens for microstructure observation were cut from the transverse section of the 1/2 height of the castings. After grinding and polishing, the specimens were etched with a solution of 100 mL ethanol, 5 g picric acid, 5 mL acetic acid and 10 mL water. The microstructures were observed by using the optical microscope and scanning electron microscope(SEM). The average grain size was measured by the linear intercept method.

3 Results

The microstructures of AZ91D alloy solidified without or with the pulsed magnetic field are shown in Fig.1. Without the PMF, a lot of large primary a-Mg dendrites are observed in the microstructure as shown in Fig.1(a); while with the PMF (α=40 V?s), the primary a-Mg becomes smaller and appears in a nearly globular shape.

Fig.1 Microstructures of AZ91D alloy: (a) Without PMF; (b) With PMF (α=40 V×s)

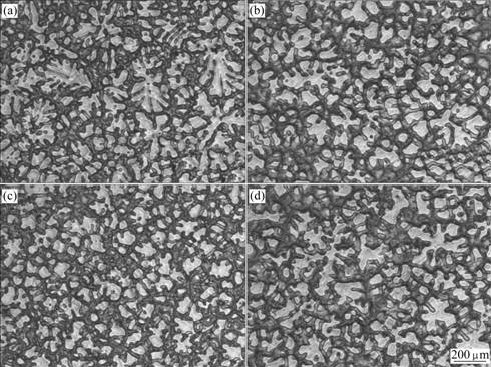

The microstructures of the AZ91D alloy solidified with different pulsed magnetic parameters are shown in Fig.2. The large dendrites in conventional casting in Fig.1(a) are not found in the specimen solidified by the PMF. The primary and second dendrites are completely restrained when the pulsed magnetic parameter is set at 40 V×s. The primary dendrite arms are short and they have a tendency to break into several parts when the pulsed magnetic parameter is 20 V×s or up to 80 V×s. When the pulsed magnetic parameter is decreased to 10 V×s, the second dendrite arms start to form and primary dendrite arms are separated from each other with the PMF, but the refining effect is not as significant as that with larger pulsed magnetic parameter.

Fig.2 Microstructures of AZ91D alloy with different pulsed magnetic parameters: (a) 10 V×s; (b) 20 V×s; (c) 40 V×s; (d) 80 V×s

Fig.3 shows the effect of pulsed magnetic parameter a on grain refinement of the AZ91 alloy. It is clear that the average grain size is dramatically decreased with the increase of the pulsed magnetic parameter when a is less than 40 V×s. However, the pulsed magnetic parameter adversely affects the grain refinement of the alloy when α is higher than 40 V×s. The optimal effect is achieved at a=40 V×s and the average grain size is 104 μm.

Fig.3 Effect of pulsed magnetic parameter on average grain size of AZ91D alloy

Fig.4 shows the distribution of average grain size on the cross section of the sample under conventional casting and under the action of pulsed magnetic field with best parameter a=40 V×s. Under conventional casting condition, the grain size tends to increase from the periphery to the center. Correspondingly, the grain size is uniform on the whole surface under pulsed magnetic field casting, which is good to the uniformity of mechanical performance on the whole casting.

Fig.4 Distribution of grain size on cross section of sample under different conditions

The microstructure of the AZ91D alloy with the PMF (a=40 V×s) is shown in Fig.5. The well-developed primary a-Mg is not observed; on the contrary, the primary a-Mg presents in a near globular shape. The fully divorced Mg17Al12 discontinuously distribute on grain boundary. There also exists a small amount of lamellar eutectic phases (second a-Mg+Mg17Al12) adjacent to fully divorced Mg17Al12 phase. The dark region in Fig.5 is the fully divorced second a-Mg phase.

Fig.5 SEM image of AZ91D alloy solidified with PMF (a=40 V×s): a Primary a-Mg; b Fully divorced Mg17Al12; c Lamellar eutectic phases (Second a-Mg+ Mg17Al12); d Fully divorced second a-Mg

The cooling curves of the AZ91D alloy are shown in Fig.6. For conventional casting, the start-solidifying and end-solidifying temperatures of the AZ91D alloy are 587 ℃ and 428 ℃, respectively. Under the action of the pulsed magnetic field with a=40 V×s, the corresponding temperatures are increased to 605 ℃ and 440 ℃, respectively. Fig.6 also indicates that the pulsed magnetic field retards temperature descending during solidification.

Fig.6 Cooling curves of AZ91D alloy

4 Discussion

Application of a pulsed magnetic field to melt will produce a vibrating effect on the melt because of the electromagnetic force produced by the interaction of the pulsed magnetic field and the melt. When the pulsed magnetic field B is imposed to the melt, an induction current I will be produced in the melt. As a result, an electromagnetic force is generated by the coupling between the induction current and the magnetic field, i.e. F=J×B. The electromagnetic force F can be decom- posed into a tangential component Ft and a radial component Fr. The component Ft causes the melt flow along tangential direction, which results in the forced convection in the melt; while the component Fr gives rise to a pressure on the melt, which can be expressed as

(1)

(1)

This pressure will cause the variation of the Gibbs free energy of liquid and solid, as expressed in the following equations[13]:

dGL=VLdp-SLdT (2)

dGS=VSdp-SSdT (3)

where GL and GS are the Gibbs free energies of the liquid and solid, respectively; SL and SS are the entropies of the liquid and solid, respectively; T is the temperature; and μ is the magnetic permeability. At the melting point Tm, the enthalpy and entropy are related as

?Hm=Tm?Sm (4)

where ?Hm is the solidification latent heat, and ?Sm is the fusion entropy. When equilibrium is achieved between the solid and liquid phase, their Gibbs free energies are all equal, i.e.

dGL=dGs (5)

Substituting Eqns.(1)-(4) into Eqn.(5), we can obtain

(6)

(6)

During the solidification of metal, both the values of ?V and ?Hm are negative, so the value of dT is positive from Eqn.(6). That is to say, the melting point of the metal will rise under the action of the magnetic field. It is the reason why the start-solidifying temperature increases from 587 ℃ to 605 ℃ with the application of the pulsed magnetic field as shown in Fig.6. This means that there will be an extra undercooling caused by the pulsed magnetic field. This undercooling will increase the nucleation rate and make grain refinement. Meanwhile, the convection accelerates the rate of heat transfer and the removal of the bulk liquid superheat, thus reduces the temperature gradient in the melt and decreases the likelihood of remelting of the solid fragments[14]. The convection also breaks off the initial solidified grains formed on the cold wall of the mould, and moves the small solid particles to the center of melt which would work as nuclei. Accordingly, crystallization could proceed simultaneously throughout the undercooled melt[15]. As a result, the growth of the columnar dendrites is prohibited, and more short dendrites are formed.

Another factor that should be pointed out is the Joule heat induced by the induction current which also influences the solidification process. Fig.6 indicates that the pulsed magnetic field increases the time of solidification by the Joule heat effect. Mg-9Al alloy has a wide range of solidification in the phase diagram. In the course of solidification, a difference in electrical resistivity appears not only between the solid and liquid but also between the different parts of solid or liquid with different Al content. The electrical resistivity for the various matters can be listed from high to low as the following order: liquid with high Al content, liquid with low Al content, solid with high Al content and solid with low Al content. So the largest difference in electrical resistivity exists between the liquid with high Al content and the solid with low Al content. Because of segregation, the liquid with high Al content is located at the root of dendritic arms, and due to the low diffusivity in solid, the solid with low Al content could be found in the earlier solidified a-Mg, i.e. the root of the dendrites. When the induction current passes through the metal pool, the most of Joule heat is produced at the solid/liquid interface of the dendrite root because the difference in electrical resistivity is the largest, which causes the remelting of the dendrite roots. The Joule heat produced at other solid/liquid interfaces of dendrite arms will spheroidize the dendrites and change their shape into globular. The liquid has a good fluidity due to the vibration under the PMF, which strongly impacts the root of the primary a-Mg dendrites during solidification. This impact effect is amplified by remelting the dendrite root. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that in the course of solidification, the liquid intensely impacts the root of the dendrites, and the Joule heat significantly affects the remelting of the root of dendrites and helps to strengthen the impact effect. As a result, grains in the melt have the tendency to be separated by the impaction of liquid, an important factor contributing to the grain refinement.

The optimized grain refinement effect is achieved under optimized a(U/w) value in Fig.3. The intensity of magnetic field is linearly increased with increasing the value of U2, so increasing the discharge voltage significantly strengthens the effect of impact and spheroidization. On the contrary, excessive discharge voltage will result in oxides intake in the bulk melt for the melt will be spilt out of the mould. Under lower pulse frequency condition, namely the a value is large (a>40 V×s), the electromagnetic power consumed by the melt is at a low level. The convection is not strong enough to remove the superheat of the melt of center region, and also the Joule heat effect and the ability to break the primary a-Mg are weakened. Under the higher pulse frequency condition, namely the a value is small (a<40 V×s), the electromagnetic power consumed by the melt is increased. The Joule heat effect is remarkable. On the other hand, for the skin effect, the electromagnetic force is concentrated to the surface of melt and the melt has the lower amplitude before full solidification, so the convection of the melt is weakened. The reason is likely to be the resonance. That is why a proper a value should be selected. Comparatively, the breaking action of the primary a-Mg is mainly caused by electromagnetic vibration other than by the Joule heat effect, so, under the higher pulse frequency condition, the effect of microstructural refinement is not as significant as the optimized pulse frequency.

5 Conclusions

1) The large dendrites in solidified structure of AZ91D alloys are changed to near globular structure under the action of a pulsed magnetic field. With the optimal pulsed-magnetic parameter, the finest as-cast microstructure of the AZ91D alloy is obtained with an average grain size of 104 mm.

2) The grain refinement caused by the pulsed magnetic field is regarded as the electromagnetic vibrating forces and Joule heat effect in the melt. The pressure caused by the electromagnetic vibrating forces results in an extra undercooling which increases the nucleation, and the forced convection reduces the temperature gradient in front of the interface, which brings on the detachment and spheroidization of dendrite arms together with the Joule heat effect induced by the induction current.

References

[1] KUROTA K, MABUCHI M, HIGASHI K. Review processing and mechanical properties of fine-grained magnesium alloys [J]. J Mater Sci, 1999, 34: 2255-2262.

[2] EMLEY E F. Principles of magnesium technology [M]. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1966: 200-210.

[3] LEE Y C, DAHLE A K, JOHN D H St. The role of solute in grain refinement of magnesium [J]. Metall Mater Trans A, 2000, 319: 2895-2906.

[4] JOHN D H St, QIAN M, EASTON M A, CAO P, HILDEBRAND Z. Grain refinement of magnesium alloys [J]. Metall Mater Trans A, 2005, 36: 1669-1679.

[5] VIV?S C. Effect of electromagnetic vibrations on microstructure of continuously cast aluminium alloys [J]. Mater Sci Eng A, 1993, 173: 169-172.

[6] VIV?S C. Effect of forced electromagnetic vibrations during the solidification of aluminium alloys (Part I): Solidification in the presence of crossed alternating electric fields and stationary magnetic fields [J]. Metall Mater Trans B, 1996, 27: 445-455.

[7] VIV?S C. Effect of forced electromagnetic vibrations during the solidification of aluminium alloys (Part ??): Solidification in the presence of collinear variable and stationary magnetic fields [J]. Metall Mater Trans B, 1996, 27: 457-464.

[8] RADJAI A, MIWA K. An investigation of the effects caused by electromagnetic vibrations in a hypereutectic Al-Si alloys melt [J]. Metall Mater Trans A, 1998, 29: 1477-1484.

[9] RADJAI A, MIWA K. Effect of intensity and frequency of electromagnetic vibration on the microstructural refinement of hypoeutectic Al-Si alloys [J]. Metall Mater Trans A, 2000, 31: 755-762.

[10] YANG Yuan-sheng, ZHOU Quan, HU Zhuang-qi. The influence of electric current pulses on the microstructure of magnesium alloy AZ91D [J]. Materials Science Forum, 2005, 488/489: 201-204.

[11] BAN Chun-yan, CUI Jian-zhong, BA Qi-xian, LU Gui-ming, ZHANG Bei-jiang. Influence of pulsed magnetic field on microstructures and macro-segregation in 2124 Al-alloy [J]. Acta Metallurgica Sinica, 2002, 15: 380-384.

[12] GAO Yu-lai, LI Qiu-shu, GONG Yong-yong, ZHAI Qi-jie. Comparative study on structural transformation of low-melting pure Al and high-melting stainless steel under external pulsed magnetic field [J]. Mater Lett, 2007, 61: 4011-4015.

[13] HU Han-qi. Solidification of metal [M]. Beijing: Metallurgical Industry Press, 1985: 274-307.

[14] GRIFFITHS W D, MCCARTNEY D G. The effect of electromagnetic stirring during solidification on the structure of Al-Si alloys [J]. Mater Sci Eng A, 1996, 216: 47-60.

[15] GRIFFITHS W D, MCCARTNEY D G. The effect of electromagnetic stirring on macrostructure and macrosegregation in the aluminium alloy 7150 [J]. Mater Sci Eng A, 1997, 222: 140-148.

Foundation item: Project(50774075) supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China; Project(2006BAE04B01-4) supported by the Key Technologies R&D Program of Ministry of Science and Technology of China

Corresponding author: YANG Yuan-sheng; Tel: +86-24-23971728; E-mail: ysyang@imr.ac.cn

(Edited by YUAN Sai-qian)