- Abstract:

- 1 Introduction▲

- 2 Experimental▲

- 3 Results and discus...▲

- 4 Conclusions▲

- References

- Figure

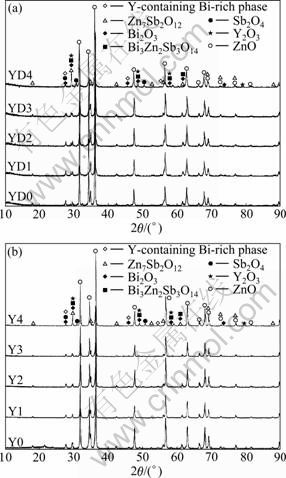

- Fig. 1 XRD patterns of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3: (a) Y(NO3)3; (b) Y2O3

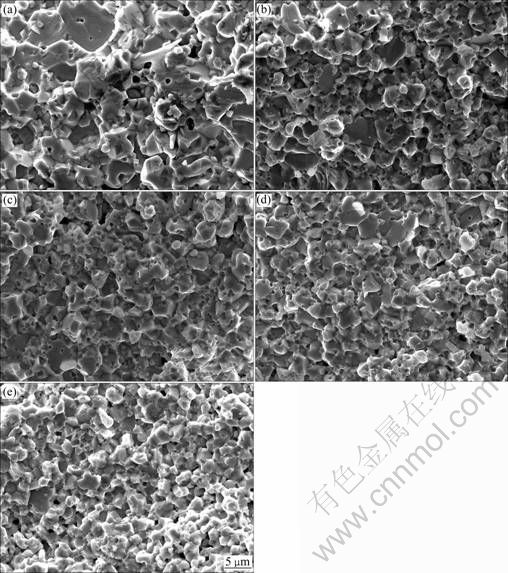

- Fig. 2 SEM images of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3: (a) YD0; (b)YD1; (c) YD2; (d) YD3; (e) YD4

- Fig. 3 SEM images of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y2O3: (a) Y0; (b)Y1; (c) Y2; (d) Y3; (e) Y4

- Fig. 4 Density of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3

- Fig. 5 Threshold voltage of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3

- Fig. 6 Nonlinear coefficient of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3

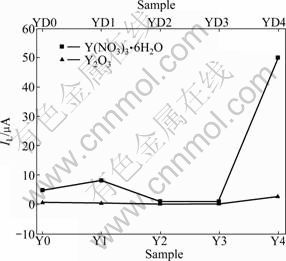

- Fig. 7 Leakage current of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3

- Fig. 8 Electric field–current density (E-J) characteristics of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3: (a) Y(NO3)3; (b) Y2O3

J. Cent. South Univ. (2012) 19: 2094-2100

DOI: 10.1007/s11771-012-1250-8![]()

Comparative characteristics of yttrium oxide and yttrium nitric acid doping in ZnO varistor ceramics

XU Dong(徐东)1, 2, 3, TANG Dong-mei(唐冬梅)1, 4, JIAO Lei(焦雷)1,

YUAN Hong-ming(袁宏明)5, 6, ZHAO Guo-ping(赵国平)1, CHENG Xiao-nong(程晓农)1, 4

1. School of Materials Science and Engineering, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang 212013, China;

2. Key Laboratory of Semiconductor Materials Science, Institute of Semiconductors,

Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100083, China;

3. State Key Laboratory of Electrical Insulation and Power Equipment (Xi’an Jiaotong University), Xi’an 710049, China;

4. Changzhou Engineering Research Institute, Jiangsu University, Changzhou 213000, China;

5. State Key Laboratory of Inorganic Synthesis and Preparative Chemistry (Jilin University), Changchun 130012, China;

6. College of Chemistry, Jilin University, Changchun 130012, China

? Central South University Press and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2012

Abstract:

The effect of different molar ratios of Y2O3 and Y(NO3)3 on the microstructure and electrical response of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics sintered at 1 000 ℃ was investigated, and the mechanism by which this doping improves the electrical characteristics of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics was discussed. With increasing amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 in the starting composition, Y2O3, Sb2O4 and Y-containing Bi-rich phase form, and the average grain size significantly decreases. The average grain size significantly decreases as the contents of rare earth compounds of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 increase. The maximum value of the nonlinear coefficient is found at 0.16% Y(NO3)3 or 0.02% Y2O3 (molar fraction) doped varistor ceramics, and there is an increase of 122% or 35% compared with the varistor ceramics without Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3. The threshold voltage VT of Y(NO3)3 and Y2O3 reaches at 1 460 V/mm and 1 035 V/mm, respectively. The results also show that varistor sample doped with Y(NO3)3 has a remarkably more homogeneous and denser microstructure in comparison to the sample doped with Y2O3.

Key words:

ceramics; varistor; rare earth; microstructure; electrical properties;

1 Introduction

Commercial varistor ceramics are usually made by a solid state process using ZnO particles with dopant oxides, such as Bi2O3, Sb2O3, Co2O3, MnO2 and Cr2O3. The mixed powder is then pressed and sintered at a high temperature [1-2]. This leads to a final microstructure, which, in the ideal situation, is constituted of a uniform grain size without porosity, segregated at grain boundaries, and homogeneously distributed crystalline secondary phases such as the spinel type Zn7Sb2O12 and pyrochlore type Zn2Bi3Sb3O14 [3-4]. The conducting ZnO is surrounded by Bi2O3 phase, that is a result from the liquid phase at the sintering temperature. Therefore, the kind, the concentration and the distribution of both the dopant and the corresponding created phases on sintering, determine the final microstructure and the electrical properties of the obtained varistor material [5-7].

Recently, it has been confirmed that it is possible to improve the electrical characteristics by the introduction of Y2O3 to the varistor ceramics [8-11]. BERNIK et al [12] reported that the microstructural and electrical characteristics of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with Y2O3 in the range from 0 to 0.9% (molar fraction) were investigated. LIU et al [13] discussed ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with 0-3% Y2O3. XU et al [14] reported Y2O3-doped ZnO-Bi2O3- based varistor ceramics sintered at 1 100 ℃. The results showed that with the addition of 0.60% Y2O3, the varistor ceramics exhibited comparatively better comprehensive electrical properties, such as the threshold voltage was 482 V/mm, the nonlinear coefficient was 34.8 and the leakage current was 0.17 μA. Y(NO3)3·6H2O-doped varistor ceramics sintered at 1 100 ℃ can be found in our previous research [2]. The results showed that the addition of 0.16% Y(NO3)3·6H2O to the ZnO–Bi2O3- based varistor ceramics produced the optimum electrical properties, namely the threshold voltage was 425 V/mm, the nonlinear coefficient was 73.9 and the leakage current was 1.78 μA. In this work, the varistor ceramics were both sintered at 1 100 ℃, but the high temperature sintering process had no advantage in both technology and economy.

In this work, the effect of Y2O3 and Y(NO3)3 on the microstructure and electrical response of ZnO–Bi2O3- based varistor ceramics sintered at a lower sintering temperature, such as 1 000 ℃,is studied, and the mechanism by which this doping improves the electrical characteristics of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics is discussed.

2 Experimental

Y2O3 doped ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor samples were gained with a composition of (96.5-x)% ZnO, 0.7% Bi2O3, 1.0% Sb2O3, 0.8% Co2O3, 0.5% Cr2O3, 0.5% MnO2 and x% Y2O3, for x=0, 0.02, 0.08, 0.20 and 1.00 (molar fraction, samples labeled as Y0, Y1, Y2, Y3 and Y4, respectively). After milling, the mixture was dried at 70 ℃ for 24 h, and then the powder was uniaxially pressed into discs of 12 mm in diameter and 2 mm in thickness.

Y(NO3)3 doped ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor samples were obtained in the proportions of (96.5-x)% ZnO, 0.7% Bi2O3, 1.0% Sb2O3, 0.8% Co2O3, 0.5% Cr2O3, 0.5% MnO2 and x% Y(NO3)3·6H2O, for x=0, 0.04, 0.16, 0.40 and 2.00 (samples labeled as YD0, YD1, YD2, YD3 and YD4, respectively). After milling, the mixture was dried at 70 ℃ for 24 h, and then the powder was calcined at 700 ℃ for 2 h in air. The calcined powder mixture went through a second milling for 1 h to eliminate large powder lumps. The powders were then dried and pressed into discs of ~12 mm in diameter and 2.0 mm in thickness.

The pressed discs were sintered in air at 1 000 ℃ (2 h dwell time), using a heating rate of 5 ℃/min and then cooled in the furnace. The sintered samples were lapped and polished and then the final samples were about 10 mm in diameter and 1.0 mm in thickness. The bulk density of the samples was measured in terms of their mass and volume [15-16].

For the characterization of DC current-voltage, the silver paste was coated on both faces of the samples and the silver electrodes formed by heating at 600 ℃ for 10 min. The electrodes were 5 mm in diameter. The voltage-current (V-I) characteristics were measured using CJP CJ1001. The nominal varistor voltages (VN) at 0.1 and 1.0 mA were measured, and the threshold voltage VT (VT=VN/t; t is the thickness of the sample in mm) and the nonlinear coefficient α (α=1/lg(V1 mA/V0.1 mA)) were determined. The leakage current (IL) was measured at 0.75VN [5-6, 8, 17-20]. The crystalline phases were identified by an X-ray diffractometry (XRD, Rigaku D/max 2200, Japan) using a Cu Kα radiation. A scanning electron microscope (SEM, FEI QUANTA 400) was used to examine the surface microstructure.

3 Results and discussion

XRD patterns of the samples doped without and with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 sintered at 1 000 ℃ for 2 h are shown in Fig. 1. It is well known that ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics typically consist of ZnO grain, spinel and intergranular Bi-rich phase. In the sample without Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3, the ZnO phase, the Zn7Sb2O12-type spinel phase, Bi3Zn2Sb3O14 and Bi2O3 phase are identified. However, in samples doped with Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3, the peak of the Zn7Sb2O12-type spinel phase becomes weaker with the addition of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 [21], and nearly vanishes when the amount of Y2O3 is increased to 1.00%, while that of the Y2O3 phase increases at the same time, which agrees with the previous research [13]. With increasing amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 in the starting composition, the Y-containing Bi-rich phase (Bi1.9Y0.1O3 phase according to JCPDF 39-0275), the Y2O3 phase and the Sb2O4 phase are revealed by the XRD analysis. The addition of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 affects the time that the mixture is spent in the liquid phase, and since it becomes longer, the vaporization of Bi2O3 from the ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics becomes significant [5, 17]. In the meantime, the doping with Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 affects the formation and decomposition of the Bi3Zn2Sb3O14 pyrochlore, which promotes the generation of the new phases, such as the Y-containing Bi-rich phase, the Y2O3 phase and the Sb2O4 phase.

Fig. 1 XRD patterns of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3: (a) Y(NO3)3; (b) Y2O3

SEM micrographs of the ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistors doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 sintering at 1 000 ℃ for 2 h are given in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. The SEM micrographs indicate that the average grain size significantly decreases as the content of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 increases. At the same time, the crystallite sizes of the Y2O3 phases become smaller but the quantities increase dramatically, and there is little different from the sample without Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 doping. The majority of the new phases is much more segregated at the multiple ZnO grain junctions than between two ZnO grains. Since the diameter of the rare-earth cation is larger than that of the Zn2+ cation, it is possible that the yttrium cation is not properly dissolved in the ZnO grains. With increasing Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 content, the Y-rich phase becomes more distributed at the multiple ZnO grain junctions and the Y-rich phase between two ZnO grains is more discontinuously distributed [8, 21-22]. At the same time, the size of the ZnO grains decreases uniformly when the amount of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 increases, which would have some influence on the electrical properties of varistor ceramics.

Fig. 2 SEM images of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3: (a) YD0; (b)YD1; (c) YD2; (d) YD3; (e) YD4

Fig. 3 SEM images of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y2O3: (a) Y0; (b)Y1; (c) Y2; (d) Y3; (e) Y4

The relative density D with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 doped ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics sintered at 1 000 ℃ for 2 h is shown in Fig. 4. The results reveal that doping with Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 has a little influence on the relative density of ZnO–Bi2O3- based varistor ceramics [2, 14]. With increasing Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 content, the relative density changes in the range of 94.1%-97.2%. With increasing the amount of Y(NO3)3, the relative density of the Y(NO3)3 doped ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics increases and then decreases. Obviously, in all cases, the extremum of the relative density is reached with 0.08% Y2O3.

The threshold voltage VT with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 doped ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics sintered at 1 000 ℃ for 2 h is shown in Fig. 5. When increasing the Y(NO3)3 content, the threshold voltage is markedly increased in the range of 535-

Fig. 4 Density of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3

1 460 V/mm along with a decrease in average grain size of ZnO (Fig. 2). When increasing the Y2O3 content, the threshold voltage is markedly increased in the range of 560-1 035 V/mm along with a decrease in average grain size of ZnO (Fig. 3). At the same time, the breakdown voltages per grain boundary of the samples are all in the range of 2-3 V, according to Refs. [23-24]. The breakdown voltage per grain boundary (Vgb) is determined from the expression Vgb=V1 mA/n=d·VT, where n is the number of grain boundaries arranged as the series between both electrodes and d is the average grain size. The threshold voltage increases as the grain size decreases. The smaller the grains size is, the higher the threshold voltage is.

Fig. 5 Threshold voltage of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3

The nonlinear coefficient α with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 of ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics sintered at 1 000 ℃ for 2 h is shown in Fig. 6. For Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 doped ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics, the nonlinear coefficient initially increases then decreases with the increase of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 content. The relationship between the nonlinear coefficient and the amount of earth oxide additive reveals an upside-down U-shape curve, which is unsymmetrical. The maximum value of the nonlinear coefficient is obtained in 0.16% Y(NO3)3 or 0.02% Y2O3 doped varistor ceramics, and it has an increase of 122% or 35% when compared with the varistor ceramics without Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3, respectively. The significant improvement of the nonlinear coefficient obtained for the varistor ceramics with Y(NO3)3 can be accounted for the microstructure uniformity and narrowed grain size distribution.

The leakage current IL with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 of ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics sintered at 1 000 ℃ for 2 h is shown in Fig. 7. It is especially meaningful that the leakage current is directly related to degradation and reliability because the leakage current should be as low as possible for various applications [22]. For Y2O3 doped ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics, when the amount of Y2O3 increases from 0% to 1.0%, the leakage current is very low and only shows little change. For Y(NO3)3 doped ZnO- Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics, when the amount of Y(NO3)3 is less than 0.40%, the leakage current shows little change, but when the amount of Y(NO3)3 is more than 0.40%, the leakage current increases sharply, by up to 50 μA, and the varistor ceramics would not be applied if there is a high leakage current. At the same time, when the ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics are doped with 2.00% Y(NO3)3, there is an increase of amount the second phases, such as Zn7Sb2O12-type spinel phase and Bi3Zn2Sb3O14-type pyrochlore phase. When the amount of the second phases is compared with the amount of the ZnO phases, the uniformity of the microstructure would become nonuniform. Consequently, the nonlinear coefficient decreases, and leakage current increases. In general, the variation of the leakage current is opposite to that of the nonlinear coefficient. The leakage current is a result of most of the electrons passing over the Schottky barrier at grain boundaries. Therefore, the lower the barrier height is, the higher the leakage current becomes, and the lower the nonlinear coefficient is [5, 19, 22, 25-26]. It is believed that the decrease in the leakage current can be attributed to an increase in activation energy (the average energy needed for electrons to overcome the Schottky barrier) and the homogeneous distribution of the limited amount of varistor dopants available in these samples.

Fig. 6 Nonlinear coefficient of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3

Fig. 7 Leakage current of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3

Figure 8 shows the electric field-current density (E-J) curves of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics with various contents of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3. The curves show that the conduction characteristics have divided into two regions: a linear region before the breakdown field and a non-linear region after the breakdown field. The sharper the knee of the curves between the two regions is, the better the non-linear properties are [27]. It is known that the sharper the knee of the curves between the linear region and the breakdown field is, the better the nonlinear characteristic is, in other words, the threshold voltage VT, the nonlinear coefficient α, and the leakage current IL are determined by the E-J curves. As can be seen from Fig. 8(a), the E-J curves show that the nonlinear properties increase in the order of YD4→YD0→YD1→ YD3→YD2, and the threshold voltage increases in the order of YD0→YD1→YD2→YD3→YD4. As can be seen from Fig. 8(b), the E-J curves show that the nonlinear properties increase in the order of Y0→Y3→ Y2→Y4→Y1, and the threshold voltage increases in the order of Y0→Y1→Y2→Y3→Y4. Narrower grain size distribution indicates more uniform and more homogeneous microstructure, which influences the uniform conducting and increasing number of active grain boundaries. The consequence is an increase of the nonlinearity coefficients and breakdown field. Varistor sample doped with 0.16% Y(NO3)3 has a remarkably more homogeneous and denser microstructure in comparison to the sample doped with 0.08% Y2O3.

Fig. 8 Electric field–current density (E-J) characteristics of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with various amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3: (a) Y(NO3)3; (b) Y2O3

4 Conclusions

1) The minute quantity of rare earth compounds can remarkably develop the properties of ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics. The average grain size significantly decreases as the content of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 increases. At the same time, the crystallite sizes of the Y2O3 phases become smaller but the quantities increase dramatically, and there is little difference from the sample without Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 doping.

2) With the increase of the content of Y(NO3)3 and Y2O3, the threshold voltage is respectively increased in the range of 535-1 460 V/mm and 560-1 035 V/mm along with a decrease in average grain size of ZnO. The maximum value of the nonlinear coefficient is found at 0.16% Y(NO3)3 or 0.02% Y2O3 doped varistor ceramics, and it has an increase of 122% or 35% compared with the varistor ceramics without Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3.

3) The leakage current is very low and only shows little change for Y2O3 doped ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics. When the content of Y(NO3)3 is less than 0.40%, the leakage current shows little change, but it will change up to 50 μA when the content of Y(NO3)3 is more than 0.40%.

4) Varistor ceramic doped with Y(NO3)3 has a remarkably more homogeneous and denser microstructure in comparison to the sample doped with Y2O3.

References

[1] DURAN P, CAPEL F, TARTAJ J, MOURE C. Low-temperature fully dense and electrical properties of doped-ZnO varistors by a polymerized complex method [J]. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 2002, 22(1): 67-77.

[2] XU Dong, CHENG Xiao-nong, YUAN Hong-ming, YANG Juan, LIN Yuan-hua. Microstructure and electrical properties of Y(NO3)3·6H2O-doped ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics [J]. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2011, 509(38): 9312-9317.

[3] WU Zhen-hong, FANG Jian-hui, XU Dong, ZHONG Qing-dong, SHI Li-yi. Effect of SiO2 addition on the microstructure and electrical properties of ZnO-based varistors [J]. International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Materials, 2010, 17(1): 86-91.

[4] XU Dong, CHENG Xiao-nong, ZHAO Guo-ping, YANG Juan, SHI Li-yi. Microstructure and electrical properties of Sc2O3-doped ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics [J]. Ceramics International, 2011, 37(3): 701-706.

[5] XU Dong, SHI Li-yi, WU Zhen-hong, ZHONG Qing-dong, WU Xin-xin. Microstructure and electrical properties of ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics by different sintering processes [J]. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 2009, 29(9): 1789-1794.

[6] XU Dong, CHENG Xiao-nong, YAN Xue-hua, XU Hong-xing, SHI Li-yi. Sintering process as relevant parameter for Bi2O3 vaporization from ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics [J]. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China, 2009, 19(6): 1526-1532.

[7] XU Dong, SHI Xiao-feng, CHENG Xiao-nong, YANG Juan, FAN Yue-e, YUAN Hong-ming, SHI Li-yi. Microstructure and electrical properties of Lu2O3-doped ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics [J]. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China, 2010, 20(12): 2303-2308.

[8] BERNIK S, MACEK S, BUI A. The characteristics of ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics doped with Y2O3 and varying amounts of Sb2O3 [J]. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 2004, 24(6): 1195-1198.

[9] NAHM C W. Effect of cooling rate on degradation characteristics of ZnO·Pr6O11·CoO·Cr2O3·Y2O3-based varistors [J]. Solid State Communications, 2004, 132(3/4): 213-218.

[10] PARK J S, HAN Y H, CHOI K H. Effects of Y2O3 on the microstructure and electrical properties of Pr-ZnO varistors [J]. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 2005, 16(4): 215-219.

[11] HOUABES M, METZ R. Rare earth oxides effects on both the threshold voltage and energy absorption capability of ZnO varistors [J]. Ceramics International, 2007, 33(7): 1191-1197.

[12] BERNIK S, MACEK S, AI B. Microstructural and electrical characteristics of Y2O3-doped ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics [J]. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 2001, 21(10/11): 1875- 1878.

[13] LIU J, HU J, HE J L, LIN Y H, LONG W C. Microstructures and characteristics of deep trap levels in ZnO varistors doped with Y2O3 [J]. Science in China Series E: Technological Sciences, 2009, 52(12): 3668-3673.

[14] XU Dong, SHI Li-yi, WU Xin-xin, ZHONG Qing-dong. Microstructure and electrical properties of Y2O3-doped ZnO-Bi2O3- based varistor ceramics [J]. High Voltage Engineering, 2009, 35(9): 2366-2370.

[15] GUNAY V, GELECEK-SULAN O, OZKAN O T. Grain growth kinetic in xCoO-6wt.% Bi2O3-(94-x) ZnO (x=0, 2, 4) ceramic system [J]. Ceramics International, 2004, 30(1): 105-110.

[16] ONREABROY W, SIRIKULRAT N, BROWN A P, HAMMOND C, MILNE S J. Properties and intergranular phase analysis of a ZnO-CoO-Bi2O3 varistor [J]. Solid State Ionics, 2006, 177(3/4): 411-420.

[17] XU Dong, TANG Dong-mei, LIN Yuan-hua, JIAO Lei, ZHAO Guo-ping, CHENG Xiao-nong. Influence of Yb2O3 doping on microstructural and electrical properties of ZnO-Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics [J]. Journal of Central South University, 2012, 19(6): 1497-1502.

[18] BERNIK S, DANEU N. Characteristics of ZnO-based varistor ceramics doped with Al2O3 [J]. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 2007, 27(10): 3161-3170.

[19] LEACH C, LING Z, FREER R. The effect of sintering temperature variations on the development of electrically active interfaces in zinc oxide based varistors [J]. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 2000, 20(16): 2759-2765.

[20] PEITEADO M, FERNANDEZ J F, CABALLERO A C. Varistors based in the ZnO-Bi2O3 system: Microstructure control and properties [J]. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 2007, 27(13/14/15): 3867-3872.

[21] HE Jin-liang, HU Jun, LIN Yuan-hua. ZnO varistors with high voltage gradient and low leakage current by doping rare-earth oxide [J]. Science in China Series E: Technological Sciences, 2008, 51(6): 693-701.

[22] NAHM C W, PARK C H. Microstructure, electrical properties, and degradation behavior of praseodymium oxides-based zinc oxide varistors doped with Y2O3 [J]. Journal of Materials Science, 2000, 35(12): 3037-3042.

[23] CLARKE D R. Varistor ceramics [J]. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 1999, 82(3): 485-502.

[24] BUENO P R, VARELA J A, LONGO E. SnO2, ZnO and related polycrystalline compound semiconductors: An overview and review on the voltage-dependent resistance (non-ohmic) feature [J]. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 2008, 28(3): 505-529.

[25] NAHM C W. The preparation of a ZnO varistor doped with and its properties [J]. Solid State Communications, 2009, 149(19/20): 795- 798.

[26] BERNIK S, BRANKOVIC G, RUSTJA S, ZUNIC M, PODLOGAR M, BRANKOVIC Z. Microstructural and compositional aspects of ZnO-based varistor ceramics prepared by direct mixing of the constituent phases and high-energy milling [J]. Ceramics International, 2008, 34(6): 1495-1502.

[27] NAHM C W. Effect of sintering temperature on nonlinear electrical properties and stability against DC accelerated aging stress of (CoO, Cr2O3, La2O3)-doped ZnO-Pr6O11-based varistors [J]. Materials Letters, 2006, 60(28): 3311-3314.

(Edited by HE Yun-bin)

Foundation item: Project(BK2011243) supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China; Project(EIPE11204) supported by the State Key Laboratory of Electrical Insulation and Power Equipment, China; Project(KF201104) supported by the State Key Laboratory of New Ceramic and Fine Processing, China; Project(KFJJ201105) supported by the Opening Program of State key Laboratory of Electronic Thin Films and Integrated Devices, China; Project(2011-22) supported by the State Key Laboratory of Inorganic Synthesis and Preparative Chemistry of Jilin University, China; Project(10KJD430002) supported by the Universities Natural Science Research Project of Jiangsu Province, China; Project(11JDG084) supported by the Research Foundation of Jiangsu University, China

Received date: 2011-10-25; Accepted date: 2012-02-10

Corresponding author: XU Dong, PhD; Tel: +86-511-88797633; E-mail: frank@ujs.edu.cn

Abstract: The effect of different molar ratios of Y2O3 and Y(NO3)3 on the microstructure and electrical response of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics sintered at 1 000 ℃ was investigated, and the mechanism by which this doping improves the electrical characteristics of ZnO–Bi2O3-based varistor ceramics was discussed. With increasing amounts of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 in the starting composition, Y2O3, Sb2O4 and Y-containing Bi-rich phase form, and the average grain size significantly decreases. The average grain size significantly decreases as the contents of rare earth compounds of Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3 increase. The maximum value of the nonlinear coefficient is found at 0.16% Y(NO3)3 or 0.02% Y2O3 (molar fraction) doped varistor ceramics, and there is an increase of 122% or 35% compared with the varistor ceramics without Y(NO3)3 or Y2O3. The threshold voltage VT of Y(NO3)3 and Y2O3 reaches at 1 460 V/mm and 1 035 V/mm, respectively. The results also show that varistor sample doped with Y(NO3)3 has a remarkably more homogeneous and denser microstructure in comparison to the sample doped with Y2O3.

- Comparative characteristics of yttrium oxide and yttrium nitric acid doping in ZnO varistor ceramics