Hot-compression constitutive relation of as-cast AZ31 magnesium alloy

SHI Ti(史褆), YU Kun(余琨), LI Wen-xian(黎文献),

WANG Ri-chu(王日初), WANG Xiao-yan(王晓艳), CAI Zhi-yong(蔡志勇)

School of Materials Science and Engineering, Central South University, Changsha 410083, China

Received 15 July 2007; accepted 10 September 2007

Abstract: In hot-compression process, the various factors have obvious effects on the deformation behavior of AZ31 magnesium alloy deformation behavior. To understand the hot-compression constitutive relation thoroughly, the stress-strain behavior of AZ31 magnesium alloy at various strain rates and different deformation temperatures were investigated under maximum strain of 60%. The microstructure of the experimental alloy was studied in the hot-compression procedure. The experimental results show that the relation of peak flow stress, strain rate and temperature can be described by Z parameter which contains Arrheniues item. The strain rate and the deformation temperature are the key parameters affecting deformation activation energy.

Key words: magnesium alloys; AZ31; hot-compression; flow stress; microstructure

1 Introduction

Magnesium alloy is the lightest structure metal material at the present time[1]. It is possible to provide boards, sticks, tubes, sectional materials and forgings with different specifications by the plastic deformation to meet the diverse structure needs. The limited number of slip systems associated with the HCP crystal structure is responsible for the poor workability of many magnesium alloys, which needs the hot-working to improve its deformation ability. But each condition of hot-working technology has obvious influence on the plastic deformation behavior of magnesium alloy[2-6]. Therefore, the research of plastic deformation behavior of magnesium alloy has the extreme significance to thorough understanding of its deformation rule.

The AZ31 magnesium alloy is a typical deformed magnesium alloy. At present, its construction relation of thermal deformation has been rarely studied. In this article the authors analyzed the flow stress of as-cast AZ31 magnesium alloy under different deforming conditions, and studied its construction relations of thermal deformation behavior. Associating with the thermal deformed microstructure, the alloy mechanical performance and the microstructure variation relations were analyzed.

2 Experimental

The chemical composition of the test AZ31 magnesium alloy is Mg-3%Al-1%Zn-0.2%Mn. The cast alloy processed were cut into test specimens with the size of d 10 mm×15 mm after 673 K, 12 h homogenization. Machine oil was added to reduce the discharge head friction force. The thermal simulation experiment was carried out on a Gleeble-1500 thermal simulation machine at strain rates of 0.01, 0.1, 1, 5 and 10 s-1. The deformation temperature is 423-723 K, and the maximum deformation degree is 60%. The alloy microstructure was observed with Polyvar—MET metallographic microscope.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Flow stress analysis and constitutive equation establishment

The true stress—strain curve of test specimen under different deformation conditions is shown in Fig.1. The peak stress is reducing obviously along with the strain rate increasing. The stress reaches the peak value more quickly with the temperature increasing. The temperature is the most obvious physical quantity influencing the flow stress. Its increasing or decreasing directly brings the increasing or reduction of the stress. Actually, in the high temperature compression process, the majority deformation energy transforms into heat. Such heat directly affects the plastic deformation, the phase transformation, the precipitation, the dynamic recovery and the dynamic recrystallization. When the strain rate increases, the dynamic recrystallization softening process time reduces, the critical shear stress and the steady-state flow stress increase[7-9]. At the strain rate  =5 s-1 and temperature below 573 K, the alloy specimens fractured.

=5 s-1 and temperature below 573 K, the alloy specimens fractured.

Fig.1 True stress—strain curves of as-cast AZ31 alloy at different strain rates: (a) =0.01 s-1; (b)

=0.01 s-1; (b) =0.1 s-1; (c)

=0.1 s-1; (c) =1 s-1; (d)

=1 s-1; (d) =5 s-1; (e)

=5 s-1; (e) =10 s-1

=10 s-1

SELLARS and TEGART[10] quoted the Arrheniues relations to describe this kind of heat activation behavior with the hyperbolic sine form including deformation activation energy Q and the temperature T:

(1)

(1)

where A, α and n are experimental constants which are independent of the temperature; R is the gas universal constant, 8.314 J/(mol?K); T is the Kelvin temperature, K; Q is the deformation activation energy. Supposing the stress and strain of AZ31 magnesium alloy obey these rules in high temperature compression process, and supposing the deformation activation energy is a parameter when the temperature is definite:

(2)

(2)

This formula in the low stress level (ασ<0.8= approaches to , and in the high stress level (ασ>1.2) approaches to

, and in the high stress level (ασ>1.2) approaches to [11], in which A1, A2, n and β are constants and independent of the temperature. The relation of α, β and n is: α=β/n. According to the empirical data under different deformation conditions, the curves of

[11], in which A1, A2, n and β are constants and independent of the temperature. The relation of α, β and n is: α=β/n. According to the empirical data under different deformation conditions, the curves of  —

— and

and  —

— have been drawn as Figs.2(a) and (b). When the deformation temperature is definite, the linear relations of the flow stress and the strain rate have been discovered by regression analysis. The average linear correlation coefficient is greater than 0.97. Extracting separately the value of n and β by Fig.2, then the value of α is determined. Quoting the Zener-Hollomon parameter:

have been drawn as Figs.2(a) and (b). When the deformation temperature is definite, the linear relations of the flow stress and the strain rate have been discovered by regression analysis. The average linear correlation coefficient is greater than 0.97. Extracting separately the value of n and β by Fig.2, then the value of α is determined. Quoting the Zener-Hollomon parameter:

(3)

(3)

where A, α and n are experimental constants, which are independent of the temperature. Deducing Eqn.(3) yields

(4)

(4)

where  ,

, .

.

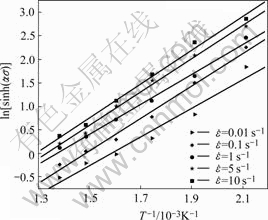

Substituting the empirical data to Eqn.(4), the curve of ln[sinh(αδ)]—1 000/T is shown in Fig.3. The linear relations of the stress and the deformation temperature have been proven, and the AZ31 magnesium alloy in high temperature compression behavior can be described by Z parameter which contains Arrheniues item. The effects of deformation temperature and the strain rate on the thermal deformation flow stress are shown in Fig.4. From the above discussion, the relations of the flow stress, strain rate and deformation temperature in high temperature deformation process satisfy the hyperbolic sine relations.

Fig.2 Relationships of stress and strain rate for AZ31 magnesium alloy: (a) as function of stress σ at different temperatures; (b)

as function of stress σ at different temperatures; (b) as function of lnσ at different temperatures

as function of lnσ at different temperatures

Fig.3 Peak stress and steady-state flow stress as function of reciprocal temperature

Deducing Eqn.(2) yields

(5)

(5)

Fig.4 Relationship of flow stress—deformation temperature— strain rate

In this equation, the straight line slope of  — ln[sinh(αδ)] is n, which is the stress index;

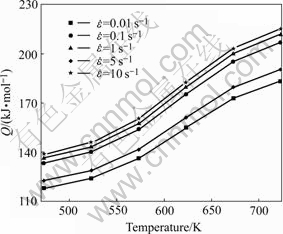

— ln[sinh(αδ)] is n, which is the stress index;  can be defined by the slope of ln[sinh(αδ)]—1 000/T straight line. The relationship of deformation activation energy Q, the temperature and the strain rate are shown in Fig.5. The deformation activation energy increases as the temperature and the strain rate increase.

can be defined by the slope of ln[sinh(αδ)]—1 000/T straight line. The relationship of deformation activation energy Q, the temperature and the strain rate are shown in Fig.5. The deformation activation energy increases as the temperature and the strain rate increase.

Fig.5 Apparent activation energy of alloy as function of temperature at different strain rates

In different strain rates and the deformation temperature, the stress σ satisfies

(6)

(6)

The approximate expression of hot-working parameter Z is deduced by substituting the mean value of Q of the cast AZ31 alloy in Eqn.(3):

(7)

(7)

The high temperature stable flow stress is insensitive to the strain. Therefore, neglecting the influence of the strain, substituting the value σ and the mean value of n in Eqn.(6), the construction relationship with the Z parameter of the peak stress, the strain rate and the temperature is expressed by

(8)

(8)

3.2 Microstructure of thermally deformed material

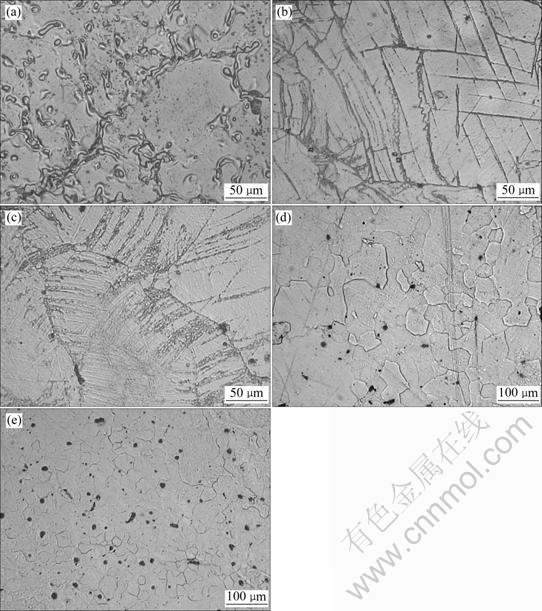

The deformation microstructures of the AZ31 magnesium alloy after deformation are shown in Fig.6. The existence of β(Mg17Al12) or β(Mg17(Al, Zn)12) in cast AZ31 alloy is obvious. From Fig.6(a), the β phase distributes in the intergranular and the dendrite net of α(Mg) as make-and-break massive. The microstructure of alloy is quite coarse after compression at 473 K, moreover it has vast scale twins, as shown in Figs.6(b) and (c). Twins cause the deformation of crystal to be very serious[12], and the crystal granularity after deformation is equivalent to the cast structure. At low temperature, the deformation mechanism of magnesium alloy is mainly the basal plane slipping and twinning[13]. Therefore in this situation the stress level is high and the material is difficult to deform. The dynamic recovery just starts at 473 K, as shown in Fig.6(b). The appearance of the zigzag intergranular is attributed to the beginning of the typical dynamic recovery[14]. Along with the strain rate increasing, many extremely tiny crystal grains appear in the alloy deformation structure, as shown in Fig.6(c). Following the temperature increase, the dynamic recovery and dynamic recrystallization become the main mechanism[15]. After deformation at 723 K, the recrystallization structure is extremely obvious, as shown in Figs.6(d) and (e). At this temperature, the stress level of material is low and enters the stable state rheopectic stage very quickly. The low strain rate will prolong the recrystallization process. And the refined DRX grain will coarsen due to longtime exposure at the high temperature with a stress rate of 5 s-1, the crystal grains after deformation are much smaller than those at 1 s-1, the grain size is even less than 10 μm.

Fig.6 Microstructures of cast AZ31 magnesium alloys before and after hot-work deformation: (a) Before deformation; (b) T=473 K, =0.1 s-1; (c) T=473 K,

=0.1 s-1; (c) T=473 K,  =5 s-1; (d) T=723 K,

=5 s-1; (d) T=723 K,  =1 s-1; (e) T=723 K,

=1 s-1; (e) T=723 K,  =5 s-1

=5 s-1

4 Conclusions

1) The peak stress of the test alloy reduces along with the temperature rise, increases along with the strain rate increase, and the peak value of the stress removes ahead of the strain along with the temperature rise.

2) When the deformation temperature is defined, the relations of the flow stress and the strain rate satisfy the linear relations, the average linear correlation coefficient is greater than 0.97. The high temperature compression behavior of the AZ31 magnesium alloy can be described by Z parameter which contains Arrheniues item.

3) The deformation activation energy increases along with temperature and strain rate increasing. The construction relationship with the Z parameter of the peak stress, the strain rate and the temperature is deduced.

4) The tested alloy just starts the dynamic recovery at 473 K. Following with the temperature rise and the strain rate decrease, the dynamic recrystallization carries on sufficiently. Above 623 K, the alloy is easy to deform.

References

[1] RAYMOND D F. The renaissance in magnesium [J]. Advanced Mater & Proc, 1998, 154(3): 31-33.

[2] LI Wen-xian. Magnesium and magnesium alloy [M]. Changsha: Central South University Press, 2005. (in Chinese)

[3] FORES F H, ELIEZER D, AGHION E. The science and technique of magnesium alloy [J]. Advance Performed Mater, 1998(5): 201-203.

[4] BYRON B C. Magnesium industry overview [J]. Advanced Mater & Proc, 1996, 150(4): 33-34.

[5] ZENG Xiao-qin, WANG Qu-dong, LU Yi-zhen. Magnesium alloy application progress [J]. Casting, 1998(11): 39-43.

[6] GALIYEV A, KAIBYSHEV R, GOTTETEIN G. Correlation of plastic deformation and dynamic recrystallization in magnesium alloy ZK60 [J]. Acta Mater, 2001, 49: 1199-1207.

[7] GLIYEV A, KAIBYSHEV R, SAKAI T. Continuous dynamic recrystallization in magnesium alloy [J]. Mater Sci Forum, 2003, 419/422: 509-514.

[8] BARNETT M R. Recrystallization during and following hot working magnesium alloy AZ31 [J]. Mater Sci Forum, 2003, 419/422: 503-508.

[9] BARNETT M R. Influence of deformation conditions and texture on the high temperature flow stress of magnesium AZ31 [J]. Journal of Light Metals, 2001(1): 167-177.

[10] TAKUDA H. Modelling on flow stress of Mg-Al-Zn alloys at elevated temperatures [J]. Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 1998, 80/81: 513-516.

[11] POIRIER J P, GUAN D L. Plasticité a haute temperature des solides cristallins [M]. Dalian: Dalian University of Technology Press, 1989. (in Chinese)

[12] YU Kun. Study on the microstructure, properties and deformation techniques of rare earth wrought magnesium alloys [D]. Changsha: Central South University, 2002. (in Chinese)

[13] POLMEAR J. Magnesium alloys and applications [J]. Mater Sci & Tech, 1994, 10: 1-14.

[14] MYSHLYAEV M M, MCQUEEN H J, MWEMBELA A, KONOPLEVA E. Twinning, dynamic recovery and recrystal-lization in hot worked Mg-Al-Zn alloy [J]. Materials Science and Engineering A, 2002, 337: 121-133.

[15] MCQUEEN H J, MYSHLAEV M M. Flow stress microstructures and modeling in hot extrusion of magnesium alloys [J]. Magnesium Technology, 2000: 355-362.

Foundation item: Project(2006BAE04B02-3) supported by the National Key Technologies R&D Program of China During the 11th Five-Year Plan Period

Corresponding author: YU Kun; Tel: +86-731-8879341; E-mail: kunyu2001@163.com

(Edited by PENG Chao-qun)