(Al63Cu25Fe12)p/A356 aluminum alloy composites prepared by spray co-deposition

LI Xiao-ping(李小平), XU Zhou(徐 洲)

Key Laboratory for High Temperature Materials and Tests of Ministry of Education,

Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200030, China

Received 28 July 2006; accepted 15 September 2006

Abstract: A novel Al-based composite material (Al63Cu25Fe12)p/A356 was prepared by spray co-deposition. It is revealed that the reinforcement of Al63Cu25Fe12 quasicrystalline particles disperses uniformly in the composite with small crystalline grain structure of about 10 μm. The reaction between the Al63Cu25Fe12 quasicrystalline particle and the matrix metal is constrained or depressed because of the high cooling velocity in the process of spray co-deposition. Compared with the composite reinforced by non-continuous ceramics particle, the aging harden behavior of the composites of (Al63Cu25Fe12)p/A356 has outstanding characteristics with less time on aging peak happening and with higher hardening rate. The mechanical properties of the composites evidently enhance except plastic strain.

Key words: spray co-deposition; Al63Cu25Fe12 quasicrystalline particle; A356 aluminum alloy; metal matrix composites; mechanical behavior

1 Introduction

Since the quasicrystal was discovered by SCHETHMEN in 1984[1], it attracted more and more interest in its application [2-4]. Quasicrystalline phases are today encountered in over 100 alloy systems, of which the majority is aluminium based alloy. But it is nearly impossible to use them as fundamental structural materials because of their intrinsic brittleness. Today, the application of quasicrystalline materials focuses on thin films, thick coatings, sinters and fillers for composites [5-7]. Especially as reinforced particles in metal composites, efforts were initiated to develop quasicrystalline reinforced Al-matrix composites which exhibit improved mechanical properties by adapting low-cost spherical reinforcement and a conventional casting process [8-11].

But it is difficult to control the reaction between the reinforcement and matrix alloy when we adopt the liquid technology such as stir-casting, squeeze-casting, saturate casting, so we use the advanced technology of Osprey forming to restrain or lower the reaction between the reinforcement and matrix alloy. Because of the rapid solidification characteristic of the spray co-deposition, the A356 composites reinforced by Al63Cu25Fe12 quasicrystalline particle with excellent properties can be prepared by Osprey deposition.

2 Experimental

The alloy with nominal composition of Al63Cu25Fe12 was prepared by gas-atomizing. Powders were subsequently sieved to the size of 0.18-0.36 mm, 0.075-0.18 mm and <0.075 mm, respectively, then annealed at 850 ℃ for 12 h in vacuum.

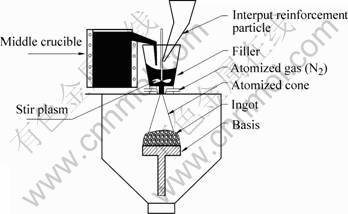

Using A356 aluminum alloy as the matrix materials (The composition of A356 matrix alloy is shown in Table 1), and the atomized Al63Cu25Fe12 powder(<0.075 mm) as the reinforced particle with the volume fraction of 10%, the A356/(Al63Cu25Fe12)p composites was success- fully prepared by spray co-deposition technology under the condition of atomizing pressure of 0.8 MPa, spraying distance of 430 mm, over-heating of 150 ℃, and molten flux of 10 kg/min. The principle sketch is shown in Fig.1.

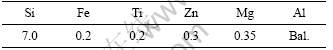

Table 1 Composition of A356 matrix alloy (mass fraction, %)

Fig.1 Principle sketch of Osprey deposition

In order to enhance the density of the composites, hot extrusion was carried out on the composites at 420 ℃, and kept for 2 h. The extrusion velocity was 1 m/min and the extrusion ratio was 11:1. Then the processes of solid solution heat-treatment at 535 ℃ for 24 h and aging at 175 ℃ were performed to the composites.

The microstructure of the sample, the phase transformation and the reaction between the matrix and particles were studied by using X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive analysis of X-ray (EDAX).

3 Results and discussion

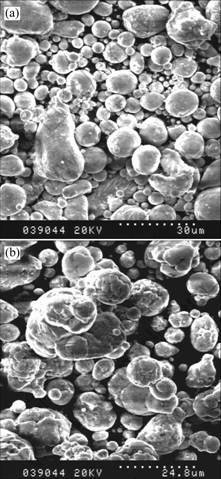

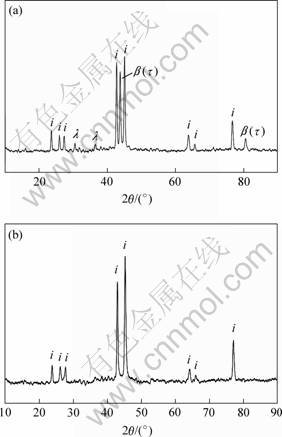

Fig.2 shows the SEM images of atomized Al63Cu25Fe12 powders before and after annealing respectively. It is obvious that the powders with larger diameter expand with mushroom-like protuberances after annealing, while little change can be found in small particles. The XRD patterns of the atomized Al63Cu25Fe12 powders before and after annealing are shown in Fig.3. The atomized powder is mainly composed of icosahedral quasicrystalline phase(i-phase), λ-Al13Fe4 and β-AlFe(Cu), consisting with the results of LEE et al [12]. After annealing the diffraction intensity of i-phase clearly increases, and almost single i-phase is obtained. For large powders, the primary λ and β phases precipitate directly from the melt, and then peritectic reaction occurs, by which the i-phase can be formed. In contrast, the cooling rate is considerably high, approximately 105 ℃/s, for the small particles, which leads to a large degree of supercooling. Therefore, i-phase forms directly from the under-cooled melt without the formation of λ and β phases. So in small powders, the primary phases observed are i-phase and small amount of τ-AlCu(Fe) phase, and little change occurs in the annealing process.

Fig.2 SEM images of atomized Al63Cu25Fe12 powder (<75 μm): (a) Before annealing; (b) After annealing

Fig.3 XRD patterns for atomized Al63Cu25Fe12 powder before(a) and after(b) annealing

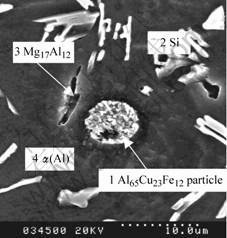

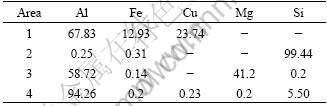

The microstructure of (Al65Cu23Fe12)p/A356 compo- sites is shown in Fig.4. The size of Al65Cu23Fe12 particles is 10-50 μm. Some holes in the larger Al65Cu23Fe12 particles are found. This proves the process of phase transformation from β-cubic phase to i-phase during annealing, and the consequent change of density. Table 2 shows the composition of different phases in the composite by the energy dispersive analysis of X-ray (EDAX). The composition of particle marked “1” is Al67.83Cu23.74Fe12.93, having little change contrasted to its initial composition. It is suggested that the reaction between the Al63Cu25Fe12 quasicrystalline particle and the matrix metal is constrained or depressed because of the high cooling velocity in the process of spray co-deposition. The size of the matrix metal α(Al) is 30-50 μm and the size of Si is 1-20 μm mostly bellow 10 μm. Furthermore, the Si phase disperses not only on the boundary of the α(Al) grain but also in the α(Al) grain. The dark phase marked “3” is Mg17Al12.

Fig.4 Microstructure of (Al65Cu23Fe12)p/A356 composites

Table 2 Composition of selected area in Fig.4 of (Al65Cu23Fe12)p/A356 composite (mole fraction, %)

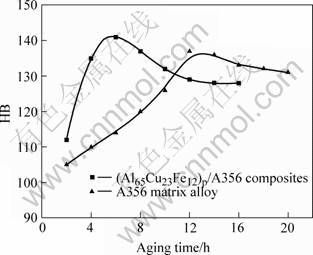

Fig.5 shows the aging-hardening curve of the composites of (Al65Cu23Fe12)p/A356 after solution heat- treatment at 535 ℃ for 24 h and aging at 175 ℃. It is obvious that the aging hardness peak and over-aging soft phenomena happen in the process of heat-treatment for composites and the matrix alloy. Compared with the composite reinforced by non-continuous ceramics particle, the aging hardening behavior of the composites of (Al63Cu25Fe12)p/A356 has two outstanding character- istics: one is the aging peak of the composites occurred at 6 h but for matrix alloy at 12 h; the other is the hardening velocity and the peak hardness of the composite higher than those of the matrix alloy. This is mostly because of the different thermal expansion coefficients between the composites and matrix alloy, which brings hot remains strain and a lot of dislocation to the matrix and prompts the process of aging hardness. This leads to the aging deposition velocity much larger than the matrix metal, and obtains the much finer crystal grain. And the energy of the finer grain prompts the process of the aging hardness.

Fig.5 Aging-hardening curves of (Al65Cu23Fe12)p/A356 composites

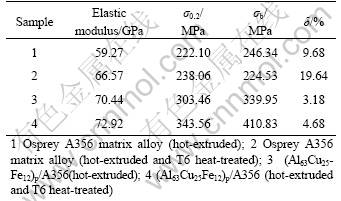

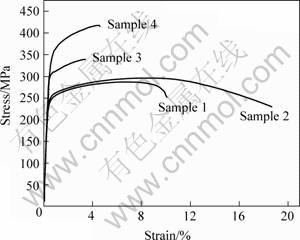

From Table 3 and Fig.6, the mechanical properties of the composites are evidently enhanced except the plastic strain(δ). After hot-extrusion and T6 (solid solution and aging) heat treatment, the σ0.2 and σb of A356 are obviously enhanced. In addition, after heat treatment of T6, the plastic strain(δ) decreases from 19.64% to 4.68%. Fig.6 shows the strain—stress curves of A356 matrix alloy and (Al63Cu25Fe12)p/A356 composites. The Osprey A356 matrix alloys has good ductibility (hot-extruded and T6 heat treated). It is a typical plastic break and very different from conventional casting ingot. After hot-extrusion and T6 treatment, the broken reaction products and quasi- crystalline particles are beneficial to the properties of composites, but because of their brittleness, the plasticity decreases.

Table 3 Mechanical properties of A356 matrix alloy and (Al63Cu25Fe12)p/A356 composite

Fig.6 Strain—stress curves of composites and matrix alloy

4 Conclusions

1) The reinforcement particles evenly disperse in the (Al63Cu25Fe12)p/A356 composite with small crystalline grain size of about 10 μm.

2) The reaction between the Al63Cu25Fe12 quasicrystalline particle and the matrix metal is suppressed or decreased in the process of spray co-deposition.

3) The aging hardness peak of the composite appears after heat treatment for 6 h, and the hardening velocity and the peak hardness of the composite are higher than those of the matrix alloy.

4) The mechanical properties of composites are much higher than those of the matrix alloy Osprey A356, σ0.2 is enhanced from 222.10 MPa to 343.56 MPa.

References

[1] KANG S S, DUBOIS J M. Compression testing of quasicrystalline materials[J]. Philos Mag A, 1992, 66: 151-163.

[2] KORSUNSKY A M, SALIMON A I, PAPE I, POLYAKOV A M, FITCH A N. The thermal expansion coefficient of mechanically alloyed Al-Cu-Fe quasicrystalline powders[J]. Scripta Mater, 2001, 44: 217-221.

[3] HUTTUNEN-SAARIVIRTA E. Microstructure, fabrication and properties of quasicrystalline Al-Cu-Fe alloys: A review[J]. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2004, 363: 150-174.

[4] JENKS C J, THIEL P A. Surface properties of quasicrystals[J]. MRS Bulletin, 1997, 22: 55-60.

[5] TKACH V I, LIMANOVSKII A I, DENISENKO S N, RASSOLOV S G. The effect of the melt-spinning processing parameters on the rate of cooling[J]. Mater Sci Eng A, 2002, 323: 91-96.

[6] BLOOM P D, BAIKERIKAR K G, JOSHUA O U, VALERIE S V. Development of novel polymer/quasicrystal composite materials[J]. Mater Sci Eng A, 2000, 294/296: 156-159.

[7] DUBOIS J M. Introduction to Quasicrystals[M]. Berlin: Springer, 1999.

[8] FLEURY E, LEE S M. CHOI G, KIM W T, KIM D H. Comparison of Al-Cu-Fe quasicrystalline particle reinforced Al composites fabricated by conventional casting and extrusion[J]. J Mater Sci, 2001, 36: 963-970.

[9] QI Y H, ZHANG Z P, HEI Z K. Phase transformation and properties of quasicrystal particle/Al matrix composites[J]. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China, 2000, 10(3): 358-363.

[10] TSAI A P, AOKI K, INOUE A. Synthesis of quasicrystalline particle-dispersed Al base composite alloys[J]. J Mater Res, 1993, 8(1): 5-7.

[11] BINER S B, SORDELET D J, LOGRASSO B K. Composite Material Reinforced with Atomized Quasicrystalline Particles[P]. US Patent, 5851317, 1998.

[12] LEE S M, JUNG J H, FLEURY E, KIM W T, KIM D H. Metal matrix composites reinforced by gas-atomised Al-Cu-Fe powders[J]. Mater Sci Eng A, 2000, 294/296: 93-98.

(Edited by YUAN Sai-qian)

Foundation item: Project(50071030) supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China

Corresponding author: LI Xiao-ping; Tel: +86-21-64485947; E-mail: lxp114@163.com